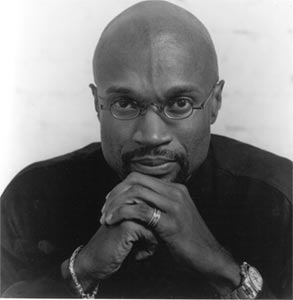

To say that Tim Adams, principal timpanist of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO), is an unusual guy is a distinct understatement. You could say he has diverse talents, but that’s not entirely accurate either. You could also describe Tim as charismatic but understated, fashionable but relaxed, good-humored but serious, and expressive but poker-faced – in short, a walking contradiction in terms. He’s tall, lanky, and shave-headed in a profession that brings to mind paunchy, white-haired, squinting old men; he has 12 pairs of glasses that he rotates according to the day’s outfit; and he wears white Armani button-downs with his cargo shorts. He eschews timpani solos in favor of percussion concertos, used to sit down for 11 p.m. jazz sets after finishing the evening’s orchestra concert, put off grad school to play keyboard and bass guitar in the rock band Exotic Birds, writes theme music for automotive Web sites, and, oh yeah, used to teach a lot of drum line. A LOT of drum line. Not quite the resume you’d expect from a highly respected orchestral timpanist.

When he plays, though, whether it’s an excerpt from Beethoven’s Ninth, a rudimental lick on a practice pad, or a sweet little jazz fill on the drumset, a few things do become very, very clear: His sincere passion for music and the absolute dedication and focus that has brought him so much success in playing and teaching. Tim has been involved in marching percussion since the eighth grade. Although Tim’s current set of jobs – including playing with the PSO, teaching as professor of percussion at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and working as a presenter and guest performer all over the country – no longer allows him enough time to participate in the pageantry arts, he is still a big fan of the activity. I sat down recently with Tim over short ribs and baked beans to talk about his myriad musical experiences and his philosophy on teaching the next generation. ET: How did you get started in music? TA: My father is a band director in Georgia. He started teaching me when I was 7, then the next year he had a student teacher who was a percussionist, and that guy taught me. The year after that I started studying with Bill Wilder of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and I studied with him until I went to college at the Cleveland Institute of Music (CIM). I also started studying with Paul Yancich my last two years of high school, and I played in the Atlanta Youth Symphony Orchestra. ET: So how does an orchestral percussionist end up playing keyboards for a rock band? TA: I was the student body president at CIM my senior year, and we needed a band for the Halloween party. So Tom Freer and Andy Kubiszewski, who were both percussionists at CIM, did it with me. I played keyboards because I had done the best in the group piano classes, Tom played drums – he had never played drumset before – and Andy did guitar and vocals. We were doing a rehearsal in a room at the college, and we needed a name, so I looked over on the board and the rehearsal list was written down. The symphony Oiseaux Exotique [by Olivier Messiaen], which means ‘Exotic Birds,” was written up there, so I looked over and said, “How about ‘Exotic Birds?'” The other guys said okay, so we were the Exotic Birds. We started playing frat parties and stuff like that, and then we pressed a single and sold 1000 copies in a week. It was at that point that we said, man, this could actually be something. So we were playing at all the colleges in the area and opened up for the Thompson Twins, and Culture Club at the Coliseum, and a lot of British bands. For a while our manager was also Michael Jackson’s assistant manager, so when we did the video, it was on all over VHI and MTV, right before “Thriller.” At the same time I was playing percussion and drum set for jingles and playing timpani for the Canton Symphony Orchestra, and after a couple years of playing in the band I went back to grad school. ET: How did you get involved in marching percussion? TA: I marched in my high school drum line from eighth grade through 12th grade, and I wrote the book for the line ninth grade through 12th grade. Summers after I graduated high school, I would come home and sub in the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and teach band camps. When I was in Florida and had just won the job for the Florida Philharmonic, I was teaching three high school drum lines and teching with Florida Wave, so I wouldn’t have to go on unemployment in the off-season. I got the job with Wave just by chance, actually; I was in the car with a friend, we heard drums, and we drove around until we found the guys playing. Ken Brooks was running rehearsal and one of his friends was a guy I’d gone to school with, so we had that connection. He said, “Hey, we really need staff,” and I said, “Sure, I’m all about it.” He said, “Okay, go teach these guys.” So I went off with the tenors and that’s how it started. I was just a tech. Officially I was one of the front ensemble guys, but I’d end up doing horn warm-up and music rehearsal and going to critique. I was all over the place. And at that time, I was teaching so much drum line that I really wanted to elevate that side of my life – my teaching. So drum corps helped me do that. And all my high school drum lines always won first place at competitions. When I moved up to Indy, when I was playing with the Indianapolis Philharmonic, I taught with one high school and did a little work with the Colts. A couple years ago, I was at a convention and ran into Brian Mason. He knew who I was and told me if I ever wanted to come check his guys out, just let him know. So I got to go on tour and consult with Phantom Regiment for a couple weeks. I’ve gotten to see the activity from both sides – from being just another tech on the bus to being Tim Adams, on tour with Phantom. And I think the activity has changed a lot from when I was that age. Kids are going in more experienced, so the learning curve is a lot quicker now. I find it impressive that the instructors can manage to keep the members focused from the second week of January up till the middle of August. ET: Do you encourage your students to march drum corps? TA: Yeah, if they want to, I tell them to go ahead and do it, especially maybe the first summer during college. I had a student in the Crossmen front ensemble a few years back, had one in SCV, another in the Cavaliers. But eventually, if the person wants to play in symphony orchestras, or become a high-end freelance performer, they have to be going to the summer festivals; they can’t take a summer off from getting better at that kind of playing, so at some point the marching has to stop. But you hear people in the orchestral world say all the time, “Oh, yeah, I marched drum corps.” The activity’s been around a long time, and a lot of people have done it. Of course, a lot who haven’t marched don’t respect the activity or give it much credit. But anyone who’s intelligent gets drum corps. They might need to be swayed, have a seed planted, but they get it. In general I think corps is a valuable activity because it introduces young kids to classical music. Whenever you can get an audience together for music, it’s valid. We’re living in sort of a cultural dark age, and people need culture that has value and content to it. Drum corps can help provide that to communities. The other thing drum corps gives people is discipline, which is an easy attribute to keep. Of course, a good teacher can also teach discipline. But by design, corps teaches discipline – even if the corps isn’t very good – and that is a wonderful trait for a human being to have. It also teaches a great degree of tolerance, due to the closeness of various people from various walks of life – people have to drop their issues with diversity in order to compete together. Everyone has to live in the same environment every day when you’re on tour, but as long as you’re with your people, life is okay. ET: What advice would you give young musicians who want to become orchestral players? TA: For any kid who wants to play in an orchestra, try to find a youth orchestra to play in. Be a part of the activity to see if you really want to do it. Listen to a lot of recordings. Listen to that kind of music all day long. The ideal is to go to a summer festival to see whether you can really do it all day every day. It’s just like marching – you can’t know what drum corps is like until you actually do drum corps. You can’t know what orchestra is like until you really go do orchestra, especially on consecutive days. That gives you an indication if you really want to do it. People say they want to do a lot of things in life, but they don’t really want to do it when they really start trying it. It always looks easy from afar. We forget people who do it professionally are experts, so it should look easy. ET: Do you have any interesting drum corps stories you want to share? TA: One night we were in Kansas City, and I had just finished tuning all the bass drums. I stretched out on the sidewalk for a nap, and a picture of me sleeping there on the sidewalk ran in the Kansas City Star the next day. I’ll never forget that. That asphalt felt just like a bed. I can still sleep anywhere!

Emily Tannert is a music education/percussion performance major at the University of Texas in Austin, Texas, and holds a journalism degree from Northwestern University. Emily graduated from the Glassmen in 2003 and was assistant tour manager for the corps in 2004 and 2005. You can contact Emily at [email protected].