Last Friday, Fanfare ran a submission from Harold Craig Barber about the proud history of African-American corps in New York City, the current state of that segment of the activity and the hopes for the future.

That very day, Fanfare received the following from Greg Wright, a tribute to his father, Bennie Wright, who was actively involved in drum corps as a life changing (and perhaps even life saving) activity for youth. Bennie Wright passed away later the same day.

After reading Mr. Barber’s article, I thought I would chime in since it is Black History Month.

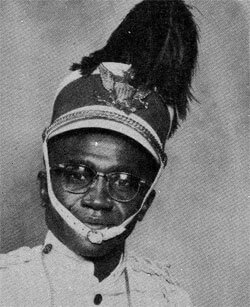

St. Stephen Drum and Bugle Corps Senior Corps was organized in 1947 and was sponsored by the St. Stephen Baptist Church of Kansas City, Mo. My father, Bennie Wright, became president of the corps in 1950. (The corps folded in the mid-1960s.) In the early 1960s, he formed a junior corps from the church, the St. Stephens Emerald Knights, and I became the drum major.

We traveled throughout the United States and Canada as a parade corps. Most of the kids had never been out of Kansas City until they joined the corps. And yes, we were sometimes hassled in some states because we were an all-African-American corps.

Some restaurants did not want to serve us and some spectators said negative things at the parades. We even stayed at a motel in a southern state were someone threw a snake at our rooms. Most of the time, though, people respected us. As kids, we did not understand everything that was going on, but it sure upset the adults.

Known as Bennie or Mr. Bennie, my father taught many kids to play bugles. He was also the bus driver for the corps. His wife Laura (Dimple) Wright—my mother—served as the president of the parent body.

Since we were in Kansas City, it was closer for us to compete in Kansas, where no other African-American corps existed. However the state of Kansas and the Great Plains Associations welcomed us.

We tried to compete in 1972. The staff of the Wichita Continental Ambassadors Drum and Bugle Corps came to Kansas City to help us put together our show, but due to a lack of interest from the parents, kids and community, it was a no-go. However, the staff of the Wichita corps put me in the car with them and took me back to Wichita were I became the assistant drum major. I had never felt so welcomed in a strange setting.

In 1973, we tried it again, but again no luck. I knew I was getting older and my drum corps life was winding down, so I ended up marching with the Argonne Rebels of Great Bend, Kan., marching in the second DCI World Championships. I was the only African-American member in the corps. The corps members all treated me well, and although there were cliques (as in any organization), each group took me to different places with them.

I was a star at shows where other African-American corps competed. The members of those corps wanted to talk to me about what it was like being in one of the great horn lines that year. I often look at the kids in our community in the summer and think how great it would be if they had the same opportunity I had.

I tried to create a corps in the area, where the drill team activity had become big. My father had given up on the drum corps activity due to the expense and lack of interest and then organized the St. Stephen Drill Team. My dad was involved in a car wreck in the early 1980s and had to have a follow-up operation. At the time he had more than 60 kids showing up for drill team practice and asked me if I could baby sit while he was in the hospital.

After seeing all the kids who were eager to do something positive, I decided to stay with the group and made them into a corps-style drill team with rifles and flags and a corps-style drum line. Within months, we were beating every drill team we competed with.

In 1989, the DCI World Championships were held in Kansas City. I found some used valve and rotor bugles and entered the ensemble in the Drum Corps International parade. Again, the city was proud to have us representing them, but we still could not get the financial support we need to compete.

Just like Mr. Barber said in his letter, I would do anything to reverse the decline of the inner city drum corps activity. This is just what the inner city youths need. If there is any organized effort to do this anywhere, please let me know at [email protected]. Mr. Bennie has indeed left a great legacy and a void that we only hope will be filled one day. We sure could use some more Mr. Bennies in the world.

Services for Mr. Bennie Wright will be held Saturday, Feb. 24, 2007 at the Stephen Baptist Church at 1414 Truman Road in Kansas City, Mo. Visitation is from 9 to 11 a.m. immediately following by the service. There will be drums and maybe even horns at the service.

The following was contributed by Mike Arato.

I was one of about eight other members of the 125 members of St. Rita’s Brassmen in the 1970s that was not of African-American descent. That was never an issue for the other members or me. The demographics made the experience even more important because in addition to being taught music and marching, I experienced a cultural enrichment that has impacted who I am today.

At age 17, when young people’s characters are still being shaped, I was fortunate enough to be in a diverse group of individuals whose focus was completely music-oriented and who took pride in the discipline required to render the excellence that we insisted upon. Nothing else mattered!

Many of us may have grown to become good, decent adults without the drum corps experience, but I firmly believe that being a part of the Brassmen while an adolescent made this a sure thing rather than a possibility. My current communication with other alums verifies this fact.

What worked then can (and should) work again today. Back in the 1970s, (as Harold Craig Barber explained in his article last week), there were many drum corps like St. Rita’s throughout the five boroughs of New York City, most of them quite good. Where have they gone? Despite the years that have passed since then, this marching and maneuvering thing remains a proven winning activity for young people. It seems like a waste to let it fade away when the only thing that can come of it is good.

Ray Schofield adds the following.

In the mid-1960s, I was a member of the Lakeland Goldenaires, a small corps from Pompton Lakes, N.J. We were one of the charter members of the Garden State Circuit, along with the Hawthorne Muchachos, Little Falls Cadets and about 10 other corps. Later we joined the Greater New York Circuit.

We regularly competed with the CMCC (first known as Minnisink) Warriors, Carter Cadets, Riversiders, the Privateers from Brooklyn and the Manhattanaires. As kids growing up in mostly white suburban communities, this was the first contact with African-Americans for many of us. We regularly went to Randall’s Island and Gaelic Park in New York City for competitions in the summer and inner city school gymnasiums for color guard events in the winter.

I’d like to say that this resulted in some wonderful friendships with black corps members, but it didn’t. For the most part, we stayed together as a group before and after the shows and didn’t socialize much with members of the other corps. But at least we had a chance to go to neighborhoods like Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant and got to see that there were other kids like us doing what we did, playing horns and drums and marching. Looking back, that was a good thing.

Editorial assistance by Michael Boo.