Coinciding with All Saints Day on the Christian calendar, here is the first of three “Fanfare” columns which take a look at church-sponsored corps and their place in the history of drum corps in America.

John Keays wrote the following:

Let’s go through the fog of time and take you down the memory lane of the Catholic Church’s drum corps glory years. There is much to remember about “God’s corps.”

The corridor between Metro Boston to the New York City area was the hub of church-sponsored corps, with a smattering of additional units sprinkled throughout the Northeast and Midwest. In general, it was akin to a cheap date—as it were—for individual parishes to start up and maintain a corps.

The churches were the center of social and recreational activity for most urban families prior to and immediately following World War ll. At the time, the cost of equipment and uniforms for a corps was low and volunteers to teach and support high, with facilities that were already in place. “Keeping the kids busy” was an easy task, as events that needed a little pageantry were available by the carload.

Transportation was nothing more than an intra-city bus or two and maybe a station wagon for gear. The number of good paying ethnic, firemen and holiday parades were year-round, plus the local politicians were always looking for “noisemakers” when fall came around. And let’s not forget the 10-day-straight parades to promote the annual parish bazaar. It was a marriage made in heaven; low overhead and parents who loved their pastors even more for keeping their kids busy.

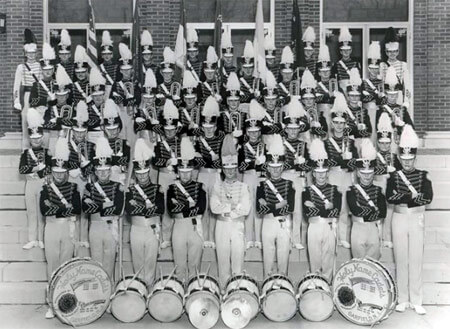

As is “the American Way,” competition became part and parcel of this activity with Garfield’s Holy Name Cadets, who, prior to World War ll, were the first of many such corps to garner national championships. Bayonne’s St. Vincent’s followed suit after the war; dominating in a way that wouldn’t be seen again until Blue Devils’ reign in the 1970s and 1980s. Newark’s Blessed Sacrament Golden Knights from the mid-1950s till the mid-1960s was a machine-like corps that beat you into submission with pure execution. When “Sac” entered the field, you knew you were competing for second place. These three corps were the competitive zenith of “God’s corps,” but it masks the depth and richness of this segment of drum corps sponsorship.

While northern New Jersey had the formula for winning big, their neighbors up the line in Boston and its surrounding towns had the magic potion for making audiences go mad with excitement. The Most Precious Blood Crusaders and St. Kevin’s Emerald Knights, in particular, never snatched the carousel’s brass ring, but their performances over time made many think there was a grand conspiracy to thwart their war with the status quo. Their insanely inventive shows left the fraternity-at-large Kelly green and red-faced with envy.

The underside of competitive church-sponsored corps was across the Hudson River in Brooklyn and Queens, with its neighborhoods and churches defined by genealogy. If you were Irish, Our Lady of Perpetual Help was your corps. If you were Italian, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Our Lady of Loretto or St. Rocco’s fit like a glove. The Swedes, Poles and Germans had their corps as well, but the St. Catherine of Sienna Queensmen and St. Rita’s Brassmen did the others one better with racially and ethnically mixed corps long before it was the cool thing to do. Each of these pre-DCI groups made a run at the New Jersey heavyweights at one time or another with some—but not complete—success.

Far from the maddening crowd, St. Joseph of Batavia (upstate New York) joined with these corps to have their place among the chosen. Many others had the briefest of moments in competitive sunshine, but for the powerhouse corps, they were mere gnats to be swatted away.

The churches did extremely well with corps for girls only, with several such units gaining the competitive attention of the boys. Long Island’s St. Ignatius gained national honors in the DCI era as a postscript to the peak period of church-sponsored corps.

This article would not be complete without mentioning several very special units. The original “toughest” corps, from a neighborhood any normal family would want to leave in a heartbeat, was St. Joseph’s of Newark. This corps gave us Father Finnigan (hard to believe, but tougher than his chargers) and Hy Dreitzer, the fountainhead brass arranger to all who followed in his wake, and last—but not least…undisputedly…no “in my honest opinion” here—the loudest horn line pound-for-pound that ever existed.

Some corps left a permanent footprint behind long after they were gone. Many who witnessed their truly unique performances wish they could magically reappear once more. I’m talking about the St. Andrews Bridgemen, folks. It can safely be said that if you didn’t love this corps, you had no joy in your soul.

Finally, there is but another Newark corps, St. Lucy’s. They went from perennial train wreck to contender over the course of one winter thanks to a young priest, Rev. Joseph Nativo. Father “Nat” types are few and far between these days but the tag of “World Changer” would be an understatement.

This world of church-sponsored drum corps slowly faded as more times than not the priest who was the spiritual and financial core of the corps was transferred to another parish and the incoming cleric just “didn’t get it.” Or, in most cases, the growing reality that local church resources just couldn’t handle the dollar demands that the emerging and more organized drum corps environment required. Many corps attempted to go forward independently, but few succeeded.

Was it a better time for drum corps? Some will argue long into the night it was. But if the truth be told, the mission of the Church changed. New doors were opening for those willing and able to enter. Much like the church halls that are the repositories of our legacies, the richness of our inheritance is silent. It is a story that needs to be told.

Editorial assistance by Michael Boo.